Nick Ford, music theory nerd.

There was a time I wouldn’t be caught dead saying something like this at a gig, “That was a Picardy Third, for all you music fans out there!” I wasn’t always this way, but I sure am now. I can’t help it. I am fascinated and love music theory. This is my journey to becoming a full blown music theory nerd.

I started learning guitar when I was 15 and was mostly self taught. I learned a great deal from growing up in a musical household, learning by ear, books, magazines, and OLGA, which stood for Online Guitar Archive. The few lessons I took showed me a little bit of reading in standard notation, but it was a local author’s method that was less than inspiring. Once my first teacher showed me a pentatonic scale and I discovered I could look up and buy Led Zeppelin tablature, I left the standard notation method in the dust.

After I left traditional lessons behind very early on, I discovered that guitar books and magazines were a great source of information. I might have a bit of a obsession though…

I got a little bit of theory in high school, but I still didn’t understand why it was important to me as a musician. When I got to college, this all changed. I decided to enroll in the music theory class, and I got my butt kicked. The first week’s assignment was to learn and memorize every major and minor scale and key signature. For people who’d been playing for a while and who had learned this, it was a breeze, but not for me. I didn’t even know what the notes of an A major chord were when I started. So, my first week of college was spent writing out every key signature and all the major and minor scales over and over.

That first semester was very rough for me. I made it through that class, but I had to work like crazy just to keep up. Because of my struggles, I didn’t take music theory 2 during my second semester. I did continue to play and practice like a fiend though. I soaked up and learned everything I could, jammed when I could find people, and even started a college band.

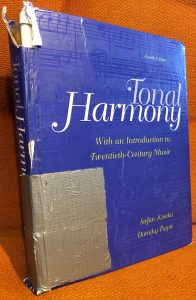

This harmony book has seen some action!

After that semester, I took an overnight job at a grocery store for the summer. I made a decision that that summer would be devoted to musical study and practice. I still had my music theory textbook, so I poured over it. I doubled down. My coworkers at my summer grocery store job looked at me like I was nuts when I studied my music theory textbook voraciously during my lunch break. I didn’t care. I was on a mission. I was going to learn this or die trying.

The following semester at college was the beginning of my sophomore year, and I couldn’t take music theory 2 yet, so I continued to study and practice. By the time the 2nd semester of Sophomore year arrived, I enrolled in the dreaded Music Theory 2. I was a sophomore in a class with freshman, but I was ok with that. Not only did I keep up with the material, I excelled. My year of intensive music theory study had done me wonders.

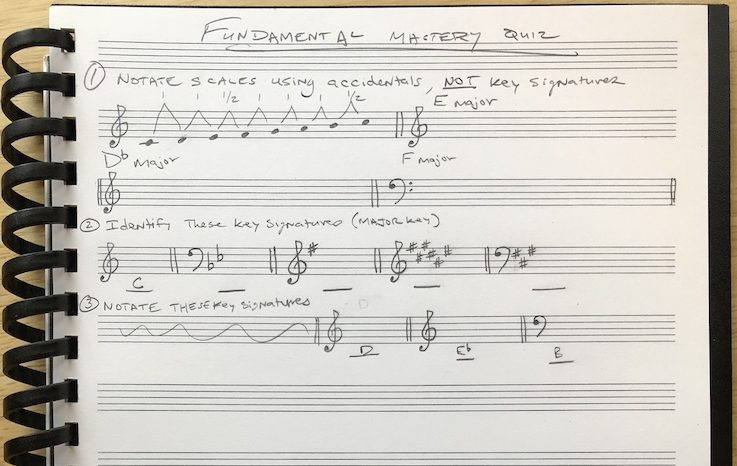

I went back for one more semester at St John’s University in Minnesota. It was this last semester there that really honed my music theory skills through a test called the “Fundamental Mastery Quiz.” In Music Theory 3, I continued to study new concepts, but the Fundamental Master Quiz was a lot of basic concepts from the first two classes in one test. The quiz counted towards my final grade, but the interesting thing is that it was taken weekly. The best score that you got in the semester would be the grade for that test for the semester. It was 40 points, and I remember that it was a timed test, so the emphasis was on not only knowing the information, but being able to confidently rattle it off quickly. So, as a result, I became very familiar and confident with fundamental music theory concepts like key signatures, scales, and harmony.

A shorter, handwritten example of the Fundamental Mastery Quiz circa the early 2000s.

I was still a psychology major, which I found fascinating, but had no idea what I wanted to do with it professionally. During the first semester of Junior year, I visited my girlfriend, now wife, Leah in Boston and dropped by Berklee College of Music. I caught a couple of end-of-semester ensemble performances where the students played tunes like the Allman Brothers’ “Jessica” and Jeff Beck’s “Freeway Jam.” I was totally blown away. My college guitar teacher at the time had recently laughed at me when I suggested a Joe Satriani tune for my final performance piece, so I felt that I found a place where I could pursue music that was more all encompassing than that of SJU, which was almost exclusively classical music. After experiencing those ensemble performances, I decided to change my life forever and become a professional musician. I transferred to Berklee College of Music the next semester.

Me, at Berklee, circa 2004. I’ve learned since then if you’re trying to look like a badass, maybe don’t wear a shirt that says “Firecracker Fun Run.”

I got in to Berklee, no problem, but I didn’t place high in music theory classes, simply because of terminology differences between SJU’s classical approach and Berklee’s jazz and pop analysis. Once I learned that a m7b5 was the same as a half diminished chord, it was easy. I even tutored people in the same class and even one person from a class ahead of me! From that point on, my music theory fundamental skills were so strong, that I absolutely devoured every music theory concept that was thrown my way easily. I knew it so well that I began to really enjoy exploring new concepts on guitar and theoretically on paper.

At Berklee, I had to take Traditional Harmony, which was literally the same book I had at St John’s University. I can’t recall why I didn’t just test out of the two classes of this. Maybe I just felt like coasting. I was so confident that I only showed up for the first and last classes of Traditional Harmony 2. I remember the teacher saying, “Oh, you’re Nick Ford. You haven’t been here all year, where were you? You’d better do well on this final test, or I’m failing you.” To which I replied, “I have all of the homework here, and I know this material cold.” I then aced the test and even finished before everyone else in the class. Looking back, I was very cocky, but I did get an A in that class!

My student: Ok, I get it. Mode Mixture is really cool. Can I please go home now?

Since graduating, my fondness for pontificating on music theory has been thrust upon band members, students, my wife (who knows what terms like Picardy Third and Andalusian Cadence are), and now to you. I have a passion for music theory that developed from determination and hard work. I have to warn my students all the time that if they get me going on music theory stuff, that they won’t get out of their lesson on time. I’m not sure if it’s when I decided to study music theory in the break room in the grocery store at 2:30am, or if it was the fundamental mastery quizzes, or if it was an arrogant student only showing up for the final exam that I became a music theory nerd. All I know is that I love this subject, and I look forward to diving into the depths of music theory on this blog and hearing from you.